Thoughts on Bringing It All Back Home

/I bought Bringing It All Back Home at the Regent Mall in Fredericton, NB in April 2000. This was before HMV made inroads into New Brunswick; Radioland and Sam the Record Man were the big chains out here at the time. I was just starting to dive deeper into music, beyond what I had been exposed to through radio and greatest hits collections. My family had to make semi-regular trips from our home in Miramichi to Fredericton at the time; I used the occasions to browse the selections the city’s record stores. Any place with enough deep catalogue titles and a decent jazz selection was preferable to the slim offerings in the Records On Wheels store at home.

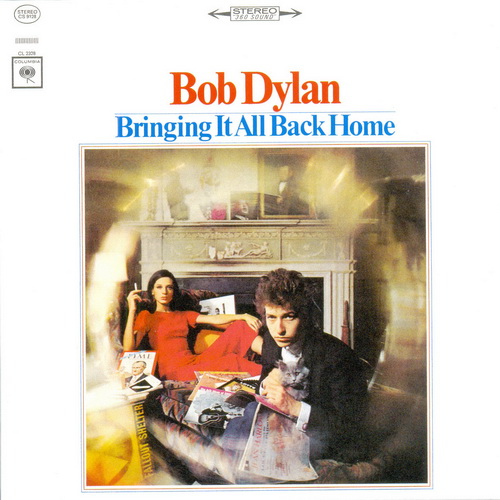

I was already into Dylan, but aside from the three Greatest Hits collections that were out at the time and a budget-line copy of Planet Waves I managed to find at the Miramichi Zellers, my appreciation of the man’s work was very surface-level. I don’t know whether it was because Bringing It All Back Home was the album with “Subterranean Homesick Blues” on it, or because it was a copy with the cellophane strip over the top that announced it as an import instead of a domestic pressing (which, at the time, had boxes and plain text replacing any art or graphic design on the back tray art), but for either reason or another, that was the one I picked as half of my 18th birthday present (Tom Waits’ Blue Valentine was the other album).

I had my Discman in the backseat with me as we drove home to Miramichi that night. The first three tracks, already familiar to me through the compilations, somehow gained more power in their original sequence. Once we hit Marysville, “Love Minus Zero/No Limit” came on; it was the first track on the album that was new to me, and the confrontational, confounding Dylan of the first three tracks gave way to the more straightforwardly beautiful words and melody. I’ll admit the next two songs didn’t make as big an impression on me at first (“Outlaw Blues” and “On The Road Again”); repeated listening revealed their charms, and both are essential to the album’s flow and breadth of scope, but between everything that came before and everything that followed, these two just felt like “ordinary” electric Dylan. Then comes “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream”, with Bob’s fit of laughter forcing him to restart the song; for the next six and a half minutes, I’m fully immersed in this funny, surrealistic shaggy-dog story.

The electric side got me interested, but the acoustic side was the real revelation. “Mr. Tambourine Man” was on Greatest Hits and “It’s All Over Now Baby Blue” was on Greatest Hits Volume II, but sandwiched between these comparatively easier-listening, subtly-accompanied cuts were the two true solo acoustic numbers on the album: “Gates of Eden” and “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)”. By the time these songs came on, the sun was down and our car had long passed through the developed outer rim of Fredericton into the wooded backcountry of central New Brunswick, and the environment seemed to go perfectly with these two stark, dark, foreboding numbers. The lack of scenery and light forced me to focus on the images conjured by Dylan’s words, guitar, and nasal husk of a voice: “Gates” was grim but straightforward, while “It’s Alright” was as claustrophobic and winding as NB Route 8.

When I listen to this album, I think about that car ride, and where I was at 18. My family still lived on Jane Street in Miramichi. I was approaching graduation from high school, often staying up late to chat with friends on ICQ. I don’t remember if I knew what I wanted back then. I’ve kept in contact with some friends from those days better than others; a few of them have only grown in their importance to my life, in ways more rewarding than I could have hoped.

I also think of how much New Brunswick has changed in the last sixteen years. Many parts of this experience aren’t possible now. Sam The Record Man and Radioland are both long gone, as is Records on Wheels and Zellers. From what I remember, Miramichi doesn’t even have its own record store anymore (Wal-Mart does not count). Highway realignments and new bypasses have changed the route between the two cities. Things have been torn down, new things built. The wooded area by the Regent Mall has become the same unwalkable and generic mess of big box stores that greets the surface-level visitor to any city. New Brunswick in some ways feels like a weird time warp compared to the rest of Canada, but playing globalization catch-up via the bland homogeneity of power centres and chain restaurants makes its cities lose their character in the name of a poor imitation of Ontario.

I’ve listened to most of Dylan’s catalogue since then, including all his major albums. There are a handful I’m not quite as familiar with (particularly the born-again period and the lower-rated 80s albums), but I know my way through the touchstones of his work. Despite this, I still can’t fully grasp what kind of a shockwave Bringing It All Back Home would have made in 1965. I can understand in the way one does with historical events placed into context, but when you have knowledge what followed afterward, the original blast becomes just another event in a sequence. It broke down the door, but it’s quaint compared to some of the work that followed: by the end of that year alone, Dylan would release Highway 61 Revisited, an album that makes Bringing It All Back Home seem more like a stepping stone than a revolution.